|

History |

|

Wars & Campaigns |

|

►Boer

War

►First

World War

►►Western

Front

►►►Trench

Warfare: 1914-1916

►►►Allied

Offensive: 1916

►►►Allied

Offensives: 1917

►►►German

Offensive: 1918

►►►Advance

to Victory: 1918

►►Siberia

►Second

World War

►►War

Against Japan

►►North

Africa

►►Italian

Campaign

►►►Sicily

►►►Southern

Italy

►►►The

Sangro and Moro

►►►Battles

of the FSSF

►►►Cassino

►►►Liri

Valley

►►►Advance

to Florence

►►►Gothic

Line

►►►Winter

Lines

►►North-West

Europe

►►►Normandy

►►►Southern

France

►►►Channel

Ports

►►►Scheldt

►►►Nijmegen

Salient

►►►Rhineland

►►►Final

Phase

►Korean

War

►Cold

War

►Gulf

War |

|

Operations |

|

|

|

Battle Honours |

|

Boer War

First World War

Western Front

Trench Warfare: 1914-1916

Allied Offensive: 1916

|

►Somme, 1916 |

1

Jul-18 Nov 16 |

|

►Albert |

.1-13

Jul 16 |

|

►Bazentin |

.14-17

Jul 16 |

|

►Pozieres |

.23

Jul-3 Sep 16 |

|

►Guillemont |

.3-6

Sep 16 |

|

►Ginchy |

.9

Sep 16 |

|

►Flers-Courcelette |

15-22

Sep 16 |

|

►Thiepval |

26-29

Sep 16 |

|

►Le Transloy |

.

1-18 Oct 16 |

Allied

Offensives: 1917

|

►Arras 1917 |

8

Apr-4 May 17 |

|

►Vimy, 1917 |

.9-14

Apr 17 |

|

►Arleux |

28-29 Apr 17 |

|

►Scarpe, 1917 |

.3-4

May17 |

|

►Hill 70 |

.15-25

Aug 17 |

|

►Messines, 1917 |

.7-14

Jun 17 |

|

►Ypres, 1917 |

..31

Jul-10 Nov 17 |

|

►Pilckem |

31

Jul-2 Aug 17 |

|

►Langemarck, 1917 |

.16-18

Aug 17 |

|

►Menin Road |

.20-25

Sep 17 |

|

►Polygon Wood |

26

Sep-3 Oct 17 |

|

►Broodseinde |

.4

Oct 17 |

|

►Poelcapelle |

.9

Oct 17 |

|

►Passchendaele |

.12

Oct 17 |

|

►Cambrai, 1917 |

20

Nov-3 Dec 17 |

German Offensive: 1918

|

►Somme, 1918 |

.21

Mar-5 Apr 18 |

|

►St. Quentin |

.21-23

Mar 18 |

|

►Bapaume, 1918 |

.24-25

Mar 18 |

|

►Rosieres |

.26-27

Mar 18 |

|

►Avre |

.4

Apr 18 |

|

►Lys |

.9-29

Apr 18 |

|

►Estaires |

.9-11

Apr 18 |

|

►Messines, 1918 |

.10-11

Apr 18 |

|

►Bailleul |

.13-15

Apr 18 |

|

►Kemmel |

.17-19

Apr 18 |

Advance to Victory: 1918

|

►Arras, 1918 |

.26

Aug-3 Sep 18 |

|

►Scarpe, 1918 |

26-30 Aug 18. |

|

►Drocourt-Queant |

.2-3

Sep 18 |

|

►Hindenburg Line |

.12

Sep-9 Oct 18 |

|

►Canal du Nord |

.27

Sep-2 Oct 18 |

|

►St. Quentin Canal |

.29

Sep-2 Oct 18 |

|

►Epehy |

3-5

Oct 18 |

|

►Cambrai, 1918 |

.8-9

Oct 18 |

|

►Valenciennes |

.1-2

Nov 18 |

|

►Sambre |

.4

Nov 18 |

|

►Pursuit to Mons |

.28 Sep-11Nov |

Second World War

War Against Japan

South-East Asia

Italian Campaign

Battle of Sicily

Southern

Italy

The Sangro and Moro

Battles of the FSSF

|

►Anzio |

22

Jan-22 May 44 |

|

►Rome |

.22

May-4 Jun 44 |

|

►Advance

|

.22

May-22 Jun 44 |

|

to the Tiber |

. |

|

►Monte Arrestino |

25

May 44 |

|

►Rocca Massima |

27

May 44 |

|

►Colle Ferro |

2

Jun 44 |

Cassino

|

►Cassino II |

11-18

May 44 |

|

►Gustav Line |

11-18

May 44 |

|

►Sant' Angelo in

|

13

May 44 |

|

Teodice |

. |

|

►Pignataro |

14-15 May 44 |

Liri Valley

|

►Hitler Line |

18-24 May 44 |

|

►Melfa Crossing |

24-25 May 44 |

|

►Torrice Crossroads |

30

May 44 |

Advance to Florence

Gothic Line

|

►Gothic Line |

25 Aug-22 Sep 44 |

|

►Monteciccardo |

27-28 Aug 44 |

|

►Point 204 (Pozzo Alto) |

31 Aug 44 |

|

►Borgo Santa Maria |

1 Sep 44 |

|

►Tomba di Pesaro |

1-2 Sep 44 |

Winter Lines

|

►Rimini Line |

14-21 Sep 44 |

|

►San Martino- |

14-18 Sep 44 |

|

San Lorenzo |

. |

|

►San Fortunato |

18-20 Sep 44 |

|

►Sant' Angelo |

11-15 Sep 44 |

|

in Salute |

. |

|

►Bulgaria Village |

13-14 Sep 44 |

|

►Pisciatello |

16-19 Sep 44 |

|

►Savio Bridgehead |

20-23

Sep 44 |

|

►Monte La Pieve |

13-19

Oct 44 |

|

►Monte Spaduro |

19-24 Oct 44 |

|

►Monte San Bartolo |

11-14

Nov 44 |

|

►Lamone Crossing |

2-13

Dec 44 |

|

►Capture of Ravenna |

3-4

Dec 44 |

|

►Naviglio Canal |

12-15 Dec 44 |

|

►Fosso Vecchio |

16-18 Dec 44 |

|

►Fosso Munio |

19-21 Dec 44 |

|

►Conventello- |

2-6 Jan 45 |

|

Comacchio |

. |

Northwest Europe

Battle of Normandy

|

►Quesnay Road |

10-11 Aug 44 |

|

►St. Lambert-sur- |

19-22 Aug 44 |

Southern France

Channel Ports

The Scheldt

Nijmegen Salient

Rhineland

|

►The

Reichswald |

8-13 Feb 45 |

|

►Waal

Flats |

8-15 Feb 45 |

|

►Moyland

Wood |

14-21 Feb 45 |

|

►Goch-Calcar

Road |

19-21 Feb 45 |

|

►The

Hochwald |

26

Feb- |

| . |

4

Mar 45 |

|

►Veen |

6-10 Mar 45 |

|

►Xanten |

8-9

Mar 45 |

Final Phase

|

►The

Rhine |

23

Mar-1 Apr 45 |

|

►Emmerich-Hoch

|

28

Mar-1 Apr 45 |

|

Elten |

. |

Korean War

|

|

Domestic Missions |

|

►FLQ

Crisis |

|

International

Missions |

|

►ICCS

Vietnam 1973

►MFO

Sinai 1986- |

|

Peacekeeping |

|

►UNTEA |

W. N. Guinea 1963-1964 |

|

►ONUCA |

C. America

1989-1992 |

|

►UNTAC |

Cambodia

1992-1993 |

|

►UNMOP |

Prevlaka

1996-2001 |

|

|

Exercises |

|

Battle of Normandy

|

The Battle of

Normandy was fought in 1944 as part of the North-West Europe

campaign, between Allied forces from the United States, the United

Kingdom, France, Canada, and Poland, and the German forces occupying

France. The actual invasion of France was the largest amphibious

operation in history, and has popularly become known as D-Day.

Canadian (and British) historians define the battle as lasting until

the start of September. American historians end the battle on 24

July 1944, the day before their forces began the breakout into Brittany.

German historians end the battle in late August.

Situation

German forces had

occupied France since the summer of 1940; utilizing large numbers of

forced labourers, massive concrete fortifications were emplaced at key

points along the entire French coastline; with garrisons in Denmark

and Norway, the German positions became known as the "Atlantic Wall."

The costly raid at Dieppe in August 1942 is widely credited as

cautioning Allied planners to ensure detailed planning, sophisticated

tactical solutions to overcoming beach defences, and overwhelming

firepower all featured into the plan.

Operation OVERLORD was

the code name for the invasion; the stated plan was to establish a

beachhead and reach the line of the Seine River by D+90 (ie 90 days

after the day of the invasion). The battle would open with a combined

airborne and seaborne assault on five designated beaches.

The Normandy invasion

began when the first pathfinders landed on Norman soil on the night of

5-6 June, leading the way for three divisions of airborne troops

(including with them the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, fighting

with the 6th British Airborne Division.) Early on the morning of 6 June

1944, six divisions came ashore, including the 3rd Canadian Infantry

Division supported by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade.

Prelude

Allied Preparations

After the dispatch of

1st Canadian Infantry Division to the Mediterranean in 1943 and the

rebuilding of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division after Dieppe, largely

from scratch, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was selected for the

assault role on the Canadian beach, code named JUNO. |

|

|

While a cross-channel

attack had been discussed since 1942, and several alternate plans

drawn up, Allied strategy revolved around landings in North Africa

in late 1942, Sicily in July 1943, and various operations in Italy in

1943 and into 1944, when the Allies finally felt ready to commit to

landing in France.

Planning began in

earnest in March 1943 by British Lieutenant General Sir Frederick E.

Morgan (who was appointed COSSAC - Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied

Commander), whose plan was developed further beginning in January 1944

by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF),

under the command of the Supreme Allied Commander, US General Dwight

D. Eisenhower, who was named to this post on 24 December 1943.

Operational command of the armies going ashore would go to General

Sir Bernard Law Montgomery, who had advised the Canadians in the UK

on matters of training, had been involved in some preliminary

planning of the Dieppe Raid, and who had commanded the 8th British

Army (to whom the 1st Canadian Division, 1st Canadian Armoured

Brigade belonged) in Sicily and later southern Italy.

The Normandy invasion

would mark the first operation in which formations passed from

control of the First Canadian Army to the Second British Army and

vice versa. For the assault, 3rd Canadian Division would be under

operational control of I British Corps. Canadian higher headquarters

would come ashore after the beachhead had been expanded. Once 2nd

British Army had established a firm foothold, First Canadian Army

would breakout and advance from a secure bridgehead. During Exercise

SPARTAN in March 1943, the First Canadian Army trained to do exactly

that, with three Canadian divisions and three British divisions

under command.

The short operating

range of Allied fighters from UK airfields, as well as the geography

of the French coast, limited the choice of landing area to either

the Pas de Calais or the Normandy beaches. The need for a large port

facility resulted in the innovative idea of bringing one across to

Normandy rather than attempting to capture one. The artificial

harbours, codenamed MULBERRY, were just one of the many logistical

successes; others included PLUTO (Pipe Line Under the Ocean) through

which vital supplies of gasoline were pumped into the bridgehead

from England. Other technical innovations would be used directly on

the beach, particularly the "funny" tanks; armoured vehicles adapted

for special purposes. |

|

| The

Atlantic Wall featured formidable obstacles to Allied invasion,

including weapons of all types and sizes sited in strong concrete

and steel fortifications. |

|

|

Elements of the 3rd Canadian Division come ashore on Juno Beach from

LCI(L) 299 of the 2nd Canadian (262nd RN) Flotilla,

optimistically bringing their issue bicycles with them. LAC 137013. |

The Canadians made great

use of the Duplex Drive (DD) tanks; regular Shermans fitted with

collapsible canvas screens and propellers to allow them to swim to shore

and provide immediate close support. Other vehicles were equipped to

assist in the passage of obstacles and demolition of strongpoints and

were used by Royal Engineers units of the British Army.

Allied intentions were

masked through successful and complex deception plans and

intelligence/counter-intelligence operations. Security was extremely

tight and Allied soldiers entered the "sausage machine" several days in

advance of the landings; these were sealed camps in which the soldiers

waterproofed vehicles, received final briefings, and were cut off from

contact with the outside world as a security precaution.

|

|

At left:

His Majesty, King George VI, inspects the Cameron Highlanders of

Ottawa (MG) on 25 April 1944. Preparations for the invasion included

new helmets, boots, and equipment such as the 1942 Battle Jerkin,

and of course a flurry of Royal Inspections. Canadian Army Photo.

At right: His

Majesty inspects self-propelled 105mm guns (dubbed "Priests") of the

divisional artillery of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on 25 April

1944. LAC 145376.

|

Objectives

-

Establish a firm lodgment

with all five assault divisions linked up by D+1 (one day after D-Day).

-

Create a firm beachhead

including the cities of Caen (to be captured on D-Day) and Cherbourg

(with its permanent port facilities)

-

Liberate Brittany, the

Atlantic ports, and advance on a line from Le Havre to Le Mans to Tours

by D+40.

- Reach the line of the Seine by D+90.

The Landings

The task on Juno Beach was

to establish a five-mile wide beachhead between Courseulles and St-Aubin-sur-Mer,

then push forward between Bayeux and Caen, penetrating eleven miles inland

to Carpiquet airfield. On their flanks, the 3rd and 50th British Divisions

would take Caen and Bayeux with the Canadians astride the road and railway

linking the two towns.

- 7th Brigade

The Brigade was delayed by

bad weather and rough seas, and faced strong opposition from enemy

strongpoints on the beach which had survived the initial bombardment, with

mines on the beach also causing considerable losses. High casualties

resulted in the fighting for Courseulles-sur-Mer and the inland villages

of Ste-Croix-sur-Mer and Banville. The brigade consolidated on its

intermediate objective near Creully by evening.

- 8th Brigade

Assault engineers arrived in a timely

manner and assisted greatly in the reduction of enemy strongpoints; the

beach and town of Bernières were taken although Bény-sur-Mer, on the road

to Caen, held out comparatively longer.

- 9th Brigade

The reserve brigade was

able to land just before noon, moving from Bernières through Bény to

Villons-les-Buissons, only four miles from Caen. The advance was stopped

short of the division's final objective, Carpiquet airfield.

- Flanks

The 3rd British Division

only came within three miles of Caen, and the 50th had been stopped short

of Bayeux by two miles. The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion fought well

as part of 6th Airborne Division, though they had been badly scattered

like most of the three airborne divisions.

Approximately 14,000

Canadians landed in Normandy on 6 June 1944, with the assault force

suffering 1,074 casualties; 359 of them had been fatal.

Early Actions

The first days ashore saw

several frantic actions as the Germans mobilized their armour in an

attempt to push the invading Allied armies back into the sea. The

defence of the beaches had been entrusted to coastal formations of

largely low calibre, tied to fortifications and given no armour and

little motorized transport. The British 2nd Army faced only a single

German division on D-Day, the 716th Infantry. Inland, however, were the

armoured divisions.

On the

front of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, the 12th SS Panzer Division

"Hitlerjugend" attempted several counter-attacks, which while

unsuccessful for the most part at seizing ground, inflicted heavy

casualties on the Canadians in the week following D-Day. After actions

at Authie, Putot-en-Bessin, Bretteville-l'Orgueilleuse, and Le

Mesnil-Patry, the division settled in to a routine of patrolling and

local actions. The first six days ashore cost the Canadian Army 196

officers and 2635 other ranks; 72 officers and 945 of whom had died.

With respect to the German counter-attacks on the Canadians, the

official Army historian summed up:

The Germans' plan

of defence had failed. They had not succeeded in mounting the great

armoured counter-offensive which was to drive the invaders into the

sea. Even a more limited attack, in which General Geyr von

Schweppenburg (whose Panzer Group West had now taken over the Caen

sector) planned to use parts of the 21st and 12th SS Panzer

Divisions under the 1st SS Panzer Corps against the Canadian front,

had to be cancelled on 10 June; and immediately afterwards a

devastating attack by aircraft...which wiped out almost his whole

staff put an end to such projects for the present, and the sector

was returned to the 1st SS Panzer Corps' control. Moreover, the

Germans remained fully convinced that a second invasion...was

probable. They therefore continued to hold (at Calais) the divisions

that might have turned the scale in Normandy.1

The record of

Canadian formations in Normandy has been controversial. New research has

suggested that the 3rd Canadian Division in particular has been

misunderstood by previous historians. The division's role may in fact

have been primarily a defensive one, to defeat the German armoured

counter-attacks - a role they performed extremely well.2

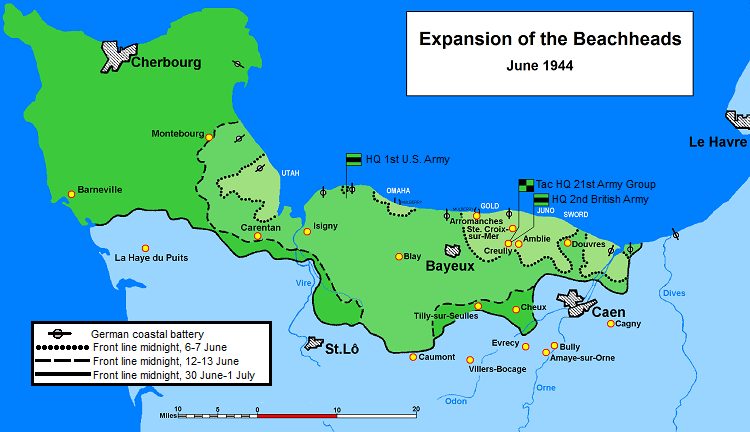

Normandy Bridgehead: June

1944

For three weeks, the 3rd

Canadian Division held a line from Putot-en-Bessin to

Villons-les-Buissons, with all three brigades in the front line and no

reserve. By the end of June, Canadian Army casualties for the month of

June totalled 226 officers and 3066 other ranks.3

The Americans on the

right flank of the invasion had fought hard to establish

themselves ashore, particularly at OMAHA Beach where an above-average

division, the 352nd, reinforced the coastal defences. Bayeux fell to the

British on D+1 (7 June) but the 21st Panzer Division effectively

intervened between the British 3rd Infantry Division and Caen. Territory

intended to marshal the 1st Canadian Army remained in German hands, and

the narrow bridgehead prevented the arrival of additional formations on

French soil. The Americans had better progress in the west; while St. Lô,

remained in enemy hands, on 18 June Cherbourg fell, and the Cotentin

Peninsula on which it sits was cleared by 1 July.

These triumphs

owed much to hard fighting by the British Second Army. Although

progress had been halted for the moment in the region immediately

about Caen, the lodgement area was somewhat extended as the result

of the determined efforts...south and south-east of Bayeux. Here in

the last week of June a bridgehead established across the Odeon, a

tributary of the Orne, seemed to offer the hope of "pinching out"

Caen by an enveloping movement. Against this threat the enemy

concentrated a tremendous mass of his very best formations....(All

told) the enemy had no fewer than eight armoured divisions on the

Anglo-Canadian front between Caumont and Caen. On 30 June, in

a directive to his British and American Army Commanders, General

Montgomery wrote: "My broad policy, once we had secured a firm

lodgement area, has always been to draw the main enemy forces in to

the battle on our eastern flank, and to fight them there, so that

our affairs on the western flank could proceed the easier." The

policy succeeded; but it meant some very hard sledding for the

British and Canadians.4

Additional Canadian forces deployed to

Normandy toward the end of June, including advance elements of the 2nd

Canadian Infantry Division, the headquarters of 2nd Canadian Corps, and

the headquarters of 1st Canadian Army.

Operation EPSOM

EPSOM was a British

operation intended

to seize Caen, with fighting lasting from 26 June to 1 July 1944;

local objectives were met but the city remained in German hands. German

counterattacks forced British units back just south of Buron.

Operation WINDSOR

On

4 July 1944, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division launched a costly assault

on Carpiquet aerodrome, originally a D-Day objective. A small force of the

12th SS Panzer Division inflicted sizeable losses on the attacking force,

including the North Shore Regiment, the Régiment de la Chaudière, the

Queen's Own Rifles and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. Supporting the operation

were the tanks of the Fort Garry Horse, assault vehicles of the Royal

Canadian Engineers (as well as a flame-throwing Crocodile), and the entire

divisional artillery. On

4 July 1944, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division launched a costly assault

on Carpiquet aerodrome, originally a D-Day objective. A small force of the

12th SS Panzer Division inflicted sizeable losses on the attacking force,

including the North Shore Regiment, the Régiment de la Chaudière, the

Queen's Own Rifles and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. Supporting the operation

were the tanks of the Fort Garry Horse, assault vehicles of the Royal

Canadian Engineers (as well as a flame-throwing Crocodile), and the entire

divisional artillery.

Operation CHARNWOOD

This operation, following

Epsom in the second week of July 1944, finally managed to push into the

city of Caen itself. The 3rd Canadian Division saw heavy combat to the

west of Caen, suffering heavily in their first major advance since the

D-Day landings; the Highland Light Infantry of Canada, for example, lost

262 men in Buron during the battle to extricate a battalion of the 25th SS

Panzergrenadier Regiment from the village.

Operation ATLANTIC

Operation

ATLANTIC was the Canadian component of Operation GOODWOOD, involving Canadian

actions in the vicinity of Caen. Their objectives including taking the

suburbs of Colombelles and Fauborg-de-Vaucelles. Both Canadian infantry divisions were

to operate on the flanks of the armoured operations as part of Operation GOODWOOD, with Canadian troops tasked to cross the Orne, clear the

suburbs, and eventually push on to the Bourguébus Ridge. Operation

ATLANTIC was the Canadian component of Operation GOODWOOD, involving Canadian

actions in the vicinity of Caen. Their objectives including taking the

suburbs of Colombelles and Fauborg-de-Vaucelles. Both Canadian infantry divisions were

to operate on the flanks of the armoured operations as part of Operation GOODWOOD, with Canadian troops tasked to cross the Orne, clear the

suburbs, and eventually push on to the Bourguébus Ridge.

On 29 June 1944, Lieutenant

General Guy Simonds activated tactical headquarters of II Canadian Corps

at Amblie, becoming operations on 11 July. The 2nd Canadian Infantry

Division came ashore in the first week of July 1944 and moved into the line

along the Orne on the right flank of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division.

The operation began on 18

July 1944, and 3rd Division moved south to Colombelles, with the 8th

Brigade battling for the suburb and the 9th Brigade passing through into

Fauborg de Vaucelles. To the east, Giberville was taken by the 7th

Brigade. On the 19th, objectives across the Orne near Cormelles were

captured.

The 2nd Division also

attacked through Fauborg de Vaucelles, coming into action for the first

time since Dieppe, and though intially managed to achieve

their objectives of clearing the suburbs of Caen across the Orne and

establishing a bridgehead south of the city, when pressed to relieve the

British armoured divisions halted in their attack on the Bourguébus

Ridge, the operation became a costly one for the units involved.

Operation SPRING

Operation SPRING was an

operation in which the

costly attacks on the Verrières Ridge occurred on 25 July 1944.

Operation TOTALIZE

The 21st Army Group decided

that after SPRING the primary task on the Canadian front would be pinning

the enemy down while the main effort would shift away from the great

German strength opposite, to the British front east of the Orne. The start

of August saw the Canadians (now serving under their own Army headquarters)

delivering local attacks, but also saw German units - now realizing that

no attack would come via Pas de Calais, as they feared - moving across the

Seine and into the battle area. Armoured units opposite the Canadians were

pulled out and redeployed to face the 3rd US Army. By 7 August only one

German armoured formation remained on the Canadian front.

By this point, the British

had made progress at the Vire and Orne Rivers, and the Canadians were

ordered forward to Falaise. On 7 August, Operation TOTALIZE went forward,

with heavy bomber support and the infantry using for the first time in

history fully tracked armoured personnel carriers. While the 3rd Canadian

Infantry Division attacked east of the Falaise road, the 2nd attacked to

the west under cover of darkness. The newly arrived German 89th Division

fought hard but the defensive line that had held out for two weeks was

finally breached, and the heights of the Verrierres Ridge were finally

seized. The second phase saw two armoured divisions - including the newly

arrived 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division - pass through. Stiff fighting

brought the Canadians to a halt - by 11 August, eight miles had been

gained, but eight still remained between the Canadians and Falaise.

The German armour that

moved away from the Canadian front was used to launch a desperate

counter-attack towards Mortain beginning on 6 August. The attack ground to

a halt within a day, and the Canadian advance on Falaise worried the

German Field Marshal in command, who was prohibited by Hitler personally

from redeploying his troops. The opportunity to encircle large parts of

the German Seventh Army now presented itself, as US armour rolled towards

Argentan from the south. The Canadian Army was ordered south; while the

armour made its preparations to move on the 14th, the 2nd Division busied

itself with preparatory attacks, crossing the Laize River at

Bretteville-sur-Laize and southward for two days, re-crossing the river at

Clair Tizon and threatening the main German defensive line along the

Falaise Road.

Operation TRACTABLE

Operation TRACTABLE was an

attempt, initiated on 14 August 1944, to meet up with American forces driving

north to close the "Falaise Gap". Initial efforts were stopped and a

renewed offensive on 16 August managed to liberate Falaise. The Gap itself

remained open while efforts were made to close it by both the US forces

from the south and Canadian and Polish forces from the north. The 1st

Polish Armoured Division linked up with the US Army at Chambois late on 20

August 1944, and the Canadians linked up with the Poles the next day.

Pursuit to the Seine

2nd Canadian Infantry

Division began to move east on 21 August, into the valley of the Seine, where

hard fighting in the Forêt de la Londe awaited the 4th and 6th Brigades.

Fierce forest fighting lasted from the morning of 27 August to the

afternoon of 29 August against well equipped enemy troops present in

strength.

August 1944 had been a

pivotal month. Not only had the German 7th Army been virtually destroyed,

but Allied landings in the south of France were coupled with the fall of

Paris. The future looked bright, and as early as 20 August, and one division

turned its gaze northwest to a familiar stretch of coast. First Canadian

Army was advised by an order on that day from 21st Army Group "I am sure

that the 2nd Canadian Division will attend to Dieppe satisfactorily."

As German forces retreated

across the Seine at the start of September, the Battle of Normandy was over. The

fighting for the Channel Ports was about to begin.

Casualties

TOTAL CANADIAN ARMY CASUALTIES - NORMANDY

BATTLE AREA

Total from 6 June 44 through 31 July 44:5

| |

Officers |

Other Ranks |

| Killed - |

136 |

1642 |

| Died of wounds - |

40 |

518 |

| Wounded - |

455 |

6525 |

| Missing - |

58 |

1116 |

| POW - |

3 |

55 |

| Total |

692 |

9856 |

(This figure represents battle casualties

but does not include 31 deaths described in the CMHQ report as

"ordinary".)

For the period 6 June to 31 August, 1,324

officers and 18,623 other ranks had become casualties, of which 340

officers and 4,285 other ranks had died.

The month of August 1944

was the costliest for Canada, not only in Normandy but for the entire

Northwest Europe campaign, with 632 officers and 8,736 other ranks

becoming casualties. Total enemy casualties are unknown but

the 1st Canadian Army collected 26,400 prisoners between 23 July (when

the army became operational) to 1 September 1944.6

Historical Assessments

Canada's battle in Normandy was a major

historic event. One chronicle summed it up thusly:

Although one major

battle remained (the Forêt de la Londe)... for all intents and

purposes the Normandy campaign ended on 21 August when the Canadians

closed the Falaise Gap...

The Canadians,

despite some subsequent criticism - none directed at the troops -

could look back with proud satisfaction on a job in Normandy very

well done. In a 77 day campaign, fought for the first 42 days by

just one division, the next 21 by two the final 13 by three the

Canadians had played a lead role greatly transcending their small

size. From start to finish they had been the spearhead of many of

the most vital battles and advances undertaken by the Anglo/Canadian

(21st) Army Group...It is noteworthy that of the 12 divisions of 21

Army Group in Normandy the 3rd Canadian Division suffered the

heaviest casualties and the 2nd Canadian, which only came into

action after Caen, the second heaviest of the entire campaign.7

General Foulkes, commander of the 2nd

Canadian Division, was quoted in the Canadian Army's Official History in

reference to those casualty rates:

The 2nd Canadian

Infantry Division had also had its troubles, accompanied by very

heavy casualties, in the bloody battles in the second half of July.

It is in order to recall again here the frank opinion of its

commander, General Foulkes: "When we went into battle at Falaise and

Caen we found that when we bumped into battle-experienced German

troops we were no match for them. We would not have been successful

had it not been for our air and artillery support. We had had four

years of real hard going and it took about two months to get that

Division so shaken down that we were really a machine that could

fight."8

The comments were later addressed by

historian Brian Reid:

In the later days

of (Operation ATLANTIC) as the 2nd Division attempted to expand the

bridgehead it had seized south of Caen onto the Verrières Ridge, it

was caught off balance by German counter-strokes and forced off the

crest of the ridge in some disorder. That much of the responsibility

for the reverse lay with two battalion commanders whose units had

broken should not obscure the fact that basic battle procedure at

the division and brigade level had broken down...Regrettably two

common features of the division's operations in Normandy appeared in

those early battles: Major General Charles Foulkes, the dour

division commander, blamed his troops for the slow progress on the

ground; and he was prone to temporarily shifting battalions between

brigades with the results one would expect when unfamiliar units are

forced to fight together...

Foulkes was a

rather unimaginative commander and one who tended to act as a postal

clerk in merely passing along orders without much

amplification...The old adage about "a poor workman always blaming

his tools" was not out of place here.9

Brereton Greenhous spoke

of the ponderous advance on Falaise and the impact of doctrine:

Among the

Canadians, generally speaking, the fault lay not with the regimental

soldier or his officers, but in the slow, deliberate British

doctrine, found in First World War experience, to which commanders

rigidly adhered. They had long over-emphasized firepower at the

expense of manoeuvre, and under-emphasized the coordination of the

three combat arms - infantry, armour and artillery - which was...the

essence of mobile warfare.

In the tangled

mountains of Italy, these ponderous tactics were sometimes

appropriate, but even there they left much to be desired on other

occasions. In Normandy, over the open, rolling fields between Caen

and Falaise, they were simply inadequate. Progress was slow; and

slowness, inevitably, led to hard fighting and heavy casualties.

Formulas that had plagued Anglo-Canadian planning since D-Day were

hardening into principle, with unfortunate results.10

This view has also been

reviewed by historians, notably Stephen Ashley Hart:

It is fair to

argue that prior to D-Day, the British and Canadians might have done

more to improve the tactical training of the soldiers fielded by the

21st Army Group...It is debatable, however, whether there existed

enough time, or sufficient expertise within the army, to train

personnel...to a significantly higher level of tactical

effectiveness. In reality, however, what the British (and Canadian

armies) needed to achieve...was to train its soldiers to an adequate

level of tactical competency sufficient to permit them to exploit

the devastation that massed Allied firepower inflicted on the enemy.

For the 21st Army Group eventually would achieve victory...not

through tactical excellence but rather through crude techniques and

competent leadership at both the operational and tactical levels.

Some historians'

criticism of the poor tactical combat performance of Anglo-Canadian

forces, moreover, has given insufficient consideration to the strong

influence that British operational technique exerted on their

activities at the tactical level...The availability of massive

firepower within the 21st Army Group would have stifled tactical

performance to some degree even if better training had produced

tactically more effective troops. Such copious firepower support

inevitably created a tactical dependency on it amongst other combat

arms. The availability of large amounts of highly effective

artillery assets made it possible...to capture enemy positions

devastated by artillery fire without having to aggressively fight

their way forward using their own weapons.11

Historians will continue

to discuss, and disagree about, many aspects of Canada's battle in

Normandy. Doctrine, strategy and senior leadership are contentious

issues that have been interpreted and re-interpreted and seem to be in

no danger of finding consensus. What is not in doubt is the cost. As

Brigadier-General Denis Whitaker, who actually fought there with the

Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, pointed out:

Modern memory has

a firm image of "suicide battalions" and futile battles of the Great

War, but we are not accustomed to thinking of Normandy in these

terms. Perhaps a single crude comparison will help to make the

point. During a single 105-day period in 1917, British and Canadian

soldiers fought the battle of Third Ypres, which included the

struggle for Passchendaele. General Haig employed forces equivalent

to those Eisenhower commanded in Normandy. When it was over, Haig's

armies had suffered 244,000 casualties, or 2,121 a day. Normandy

cost the Allies close to 2,500 casualties a day, 75 per cent of them

among the combat troops at the sharp end who had to carry the battle

to the enemy.12

Deployment Schedule

|

Formation/Unit |

Parent Formation |

Arrival in France |

Entered Front Line |

Notes |

|

1st Canadian Army |

21 Army Group |

June 1944 |

23 July 1944 |

|

|

2nd Canadian Corps |

2nd Brit Army/1st Cdn Army |

29 June 1944 |

11 July 1944 |

|

|

2nd Canadian Infantry

Division |

2nd Canadian Corps |

7 July 1944 |

11 July 1944 |

|

|

3rd Canadian Infantry

Division |

1st Brit Corps/2nd Cdn Corps |

6 June 1944 |

6 June 1944 |

|

|

2nd Canadian Armoured

Brigade |

1st Brit Corps/2nd Cdn Corps |

6 June 1944 |

6 June 1944 |

Independent Brigade |

|

4th Canadian Armoured

Division |

2nd Canadian Corps |

July 1944 |

31 July 1944 |

|

|

1st Canadian Parachute

Battalion |

British 6th Airborne

Division |

6 June 1944 |

6 June 1944 |

Withdrawn 6 September |

|

1st Canadian Armoured

Personnel Carrier Squadron |

1st Canadian Army |

28 August

1944 |

2 September

1944 |

Formed in France |

Battle Honours

The following

Battle Honours were granted for Canadian units participating in the

Battle of Normandy:

-

Normandy Landing

-

Authie

-

Putot-en-Bessin

-

Bretteville-l'Orgueilleuse

-

Le Mesnil-Patry

-

Carpiquet

-

Caen

-

The Orne or The Orne (Buron)

-

Bourguébus Ridge

-

Faubourg de Vaucelles

-

St. André-sur-Orne

-

Maltot

-

Verrières Ridge - Tilly-la-Campagne

-

Falaise

-

Falaise Road

-

Quesnay Wood

-

Clair Tizon

-

The Laison

-

Chambois

-

St. Lambert-sur-Dives

-

Dives Crossing

-

Forêt de la Londe

-

The Seine, 1944

Dramatizations

- The Longest Day (1962). The only

Canadian content seems to be a dramatization of two German pilots

strafing Juno Beach, and the theme song by Paul Anka which was later

authorized as the Regimental March of The Canadian Airborne Regiment.

Notes

-

Stacey, C.P. Official History of

the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III: The Victory

Campaign: The Operations in North-west Europe 1944-45

(Queen's Printer, Ottawa, ON, 1960) p.141

-

See Milner,

Stopping the Panzers

-

Stacey, C.P. Canada's Battle in Normandy: The

Canadian Army's Share in the Operations 6 June - 1 September 1944

(King's Printer, Ottawa, ON, 1946) p.75

-

Ibid, pp.79-80. The remarks by General

Montgomery have come under scrutiny and much debate. For example, see

Carlos d'Este, Decision in Normandy "What Montgomery

absurdly attempted to portray as the end result of a deliberate master

plan was, in reality, one of the most untidy series of operations he

ever conducted."

-

(Canadian Military Headquarters file

22/Casualty/1/2 - A.G. (Stats), C.M.H.Q., 14 Aug 44)) quoted in Canadian Military Headquarters Report: "OPERATION

"OVERLORD" and its Sequel. Canadian Participation in the Operations in

N.W. Europe 6 Jun - 31 Jul 44 (Prelim Report). (Report No. 131,

revised edition, 1945)

-

Stacey, Ibid, p.158

-

McKay, A. Donald Gaudeamus Igitur

"Therefore Rejoice" (Bunker to Bunker Books,

Calgary, AB, 2005) ISBN 1894255534 p.180

-

Stacey, Victory Campaign, Ibid, p.276

-

Reid, Brian. No Holding Back:

Operation Totalize, Normandy, August 1944. (Robin Brass

Studio, Toronto, ON, 2005) ISBN 1-896941-40-0 pp.47-48

-

Greenhous, Brereton "The

Victory Campaign 1944-45" We Stand on Guard: An Illustrated

History of the Canadian Army (Ovale Publications, Montreal,

PQ, 1992) ISBN 2894290438 p.303

-

Hart, Stephen Ashley Colossal Cracks: Montgomery's

21st Army Group in Northwest Europe, 1944-45 (Stackpole Books,

Mechanicsburg, PA, 2007) ISBN 978-0-8117-3383-0 pp.178-179

-

Whitaker, Denis and Shelagh Whitaker (with Terry Copp)

Victory at Falaise: The Soldier's Story (HarperCollins

Publishers Ltd., Toronto, ON, 2000) ISBN 0-00-200017-2

p.312

References

-

Barris, Ted. Juno : Canadians at

D-Day, June 6, 1944 (Toronto : T. Allen Publishers, 2004) xxii,

307 p., [24] p. of plates : ill., maps ISBN: 0887621333

-

Copp, Terry and Robert Vogel Maple

Leaf Route: Caen (Alma, ON 1983) 119pp ISBN 0919907016

-

Copp, Terry and Robert Vogel Maple

Leaf Route: Falaise (Alma, ON 1983) 143pp ISBN 0919907024

-

English, John The Canadian Army

and the Normandy Campaign: A Study of Failure In High Command (Praeger,

New York, NY 1991) 347pp. ISBN 027593019X

-

Granatstein, J.L. and Desmond Morton. Bloody Victory: Canadians and the D-Day Campaign 1944 (Lester

& Orpen Dennys, Toronto, ON 1984) 240pp ISBN 0886190460

-

Milner, Marc Stopping the

Panzers (University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS,

2014) ISBN 978-0-7006-2003-6 400pp.

-

Reid, Brian A. No Holding Back

(Robin Brass Studio, 2004) 491pp ISBN 1896941400

-

Whitaker, Denis and Shelagh Whitaker

with Terry Copp The Soldier's Story: Victory at Falaise

(HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., Toronto, ON 2000) 372pp ISBN 0002000172

|